Introduction

September is a notoriously volatile month and it certainly held true to form in 2021. Stocks sold off during a seasonally weak period of the calendar as market uncertainty grew. The S&P 500 declined by more than -5% from its previous high while the Nasdaq index fell by more -7% from its prior peak.

We have long held the view that a couple of unusual factors would allow economic and earnings growth to surprise on the upside. Coming out of the Covid recession, we had an unusually strong U.S. consumer and we had unusually massive policy stimulus. In the first half of the year, they did propel growth higher than consensus expectations.

But the tide seems to have turned as the list of investor concerns has grown steadily in recent weeks.

There is a growing fear that supply chain constraints may keep inflation high and raise the specter of stagflation. The proposed reconciliation bill comes bundled with higher taxes that are generally restrictive for growth. Fiscal and monetary policy is approaching an inflection point and investors are now focusing on an anticipated deceleration of growth. Investors also worry that historically high stock valuations may be at risk if growth slows down dramatically.

We focus on the following discussion points to answer one key question.

- Inflation

- Spending and taxes

- Inflection in stimulus

- Deceleration and valuations

Are these potential headwinds likely to become major disruptors of growth in the coming months? Or will they merely be distractions on a bumpy road to recovery?

We begin our discussion with some brief remarks on a couple of other investor concerns that appear to be fading at the time of this writing. The Delta variant triggered a third wave of the coronavirus and stalled economic activity in the third quarter. However, we appear to have peaked in daily new cases, hospitalization rates and the incidence of deaths and a third round of re-opening may well lie ahead of us in the fourth quarter.

The perennial debate on the debt ceiling surfaced again in September and created angst and uncertainty among investors. At this moment of time, it appears that the Senate has reached an agreement to raise the debt ceiling through early December. We believe that a more permanent deal to resolve this manufactured crisis will also be negotiated in the coming weeks.

Inflation

Inflationary pressures started to build up after vaccination rates gathered momentum in early 2021. The initial spike in inflation was attributed to two pandemic-related effects – pent-up demand and supply chain disruptions.

The U.S. consumer has remained strong through the Covid recession. Disposable incomes are higher as a result of fiscal stimulus. Consumer net worth has soared from higher savings, rising stock prices, a red-hot housing market and low interest rates. The inability to travel or even move freely inhibited spending during the pandemic. The ability to do so after reopening, along with higher savings and incomes, has unleashed significant pent-up demand for goods and services.

At the same time, global supply chains have been in disarray after being brutally disrupted during the pandemic. Lengthy factory shutdowns in Asia and snarled shipping traffic have created a constant shortage of key components for manufacturing. Labor has also remained in short supply and contributed to wage increases.

Many had expected these pandemic effects to be shortlived and, therefore, for inflation to remain transitory. It is now increasingly clear that “transitory” needs to be recalibrated as inflation is proving to be more persistent than initially expected.

As growth begins to decelerate at the same time that inflation remains stubbornly high, investors have now started to worry about stagflation. We will discuss the deceleration of growth in later sections. We set out here to assess the outlook for inflation in the short term and over the long run.

We first rule out the possibility of runaway inflation similar to the levels seen in the 1970s. We do not see any parallels to the types of supply side shocks that were experienced in the oil and food markets back then.

We narrow down our choices of likely inflation regimes to either stubborn or transient and conclude that the answer is both over a 3-year horizon. We explain the rationale and implications of our view.

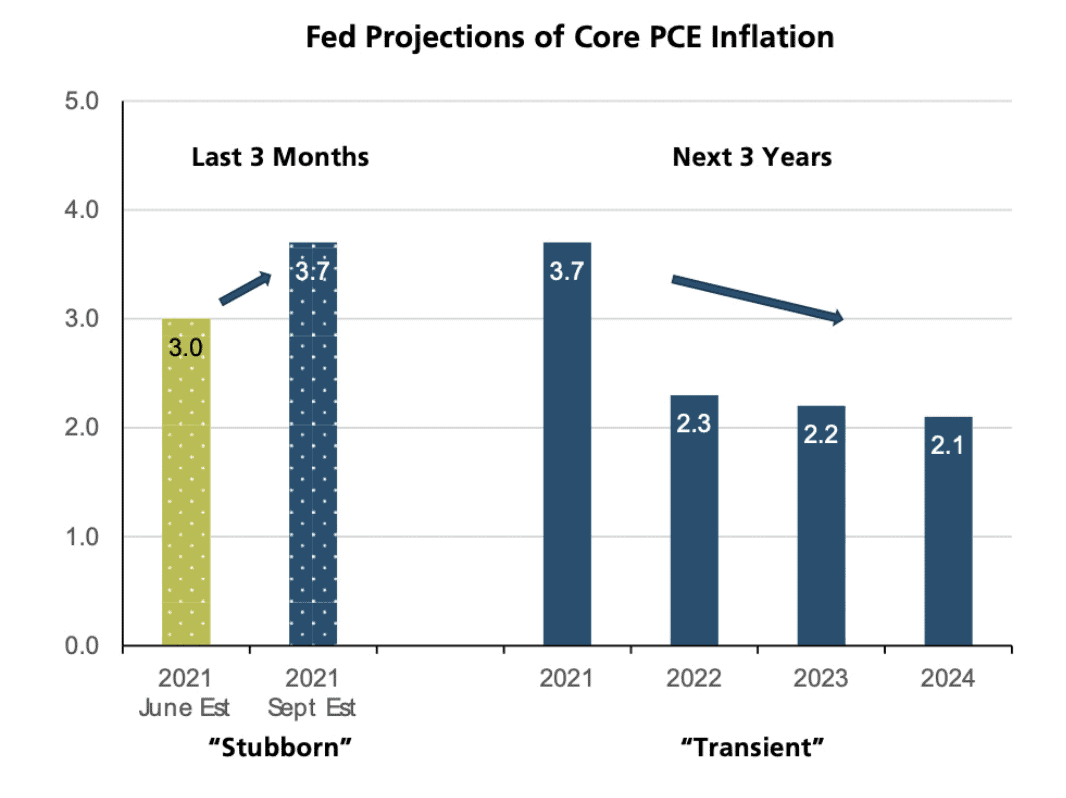

We show the Fed’s revised outlook on inflation in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Fed Projections of Core PCE Inflation

The Fed uses the Personal Consumption Expenditures metric as its preferred inflation gauge. The left chart in Figure 1 shows how their forecast for core inflation in 2021 has risen in the last 3 months. It now stands at 3.7% in September … up from 3.0% in June.

On the other hand, their forecasts for the next 3 years in the right chart above show a significant decline. Core inflation is projected to be just above 2% in 2022, 2023 and 2024.

We believe that the Fed’s outlook for core inflation at 2.3% in 2022 is overly benign. We think instead that inflation will remain sticky and stubborn for more than just a few more months. We expect core inflation to be 3% or higher for the next 12 months or so.

Month-over-month inflation has come down in pandemic-affected sectors like cars, airfares and hotels in recent weeks. But that decrease has been offset by an uptick in wage and rent inflation. And any easing of supply-side constraints in the near term will likely be offset by greater demand as the Delta variant continues to recede.

We, therefore, believe that the decline in inflation will be more gradual than the rate at which it spiked up. We are also not troubled by core inflation levels of around 3% in the near term. We know empirically that Price to Earnings (PE) ratios for stocks do well when inflation rises to around 3% from disinflationary levels against a backdrop of higher growth.

Over a longer 3-year horizon, we believe that inflation will end up being transient and recede towards 2.5%. There are powerful secular forces related to technology, demographics and global competition that will inevitably contain inflation in the long run. We are aligned with the Fed over the longer term and the markets which are pricing in lower inflation expectations in the future.

Spending and Taxes

The proposed reconciliation bill for social welfare has generated both support and opposition. Proponents of the bill view it as a significant investment in human and environmental infrastructure with the longterm benefits of greater social equality and a more sustainable planet.

Critics, however, worry about the implications of both higher spending and higher taxes. Some fear that more spending will exacerbate an already significant debt burden and others fret that higher taxes will be restrictive to growth.

We address the topic with a very narrow focus.

We comment simply on the economic impact of higher taxes and higher spending without any adherence to a political or philosophical ideology. We also steer clear of any tax advice.

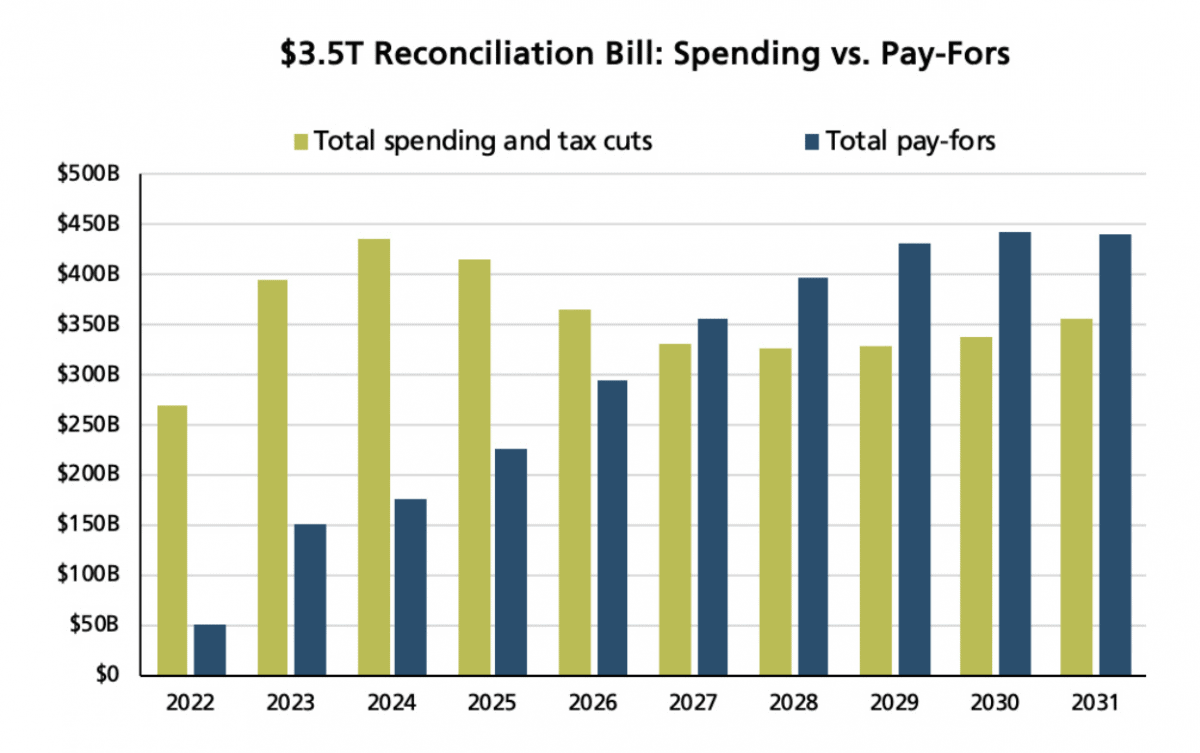

The $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill has funding for education, housing, child and elder care, healthcare and climate change. The green bars in Figure 2 below show proposed outlays for spending and tax cuts over each of the next ten years.

Figure 2: $3.5T Reconciliation Bill: Spending vs. Pay-Fors

These programs offer direct and indirect social, environmental and economic benefits. For example, there is research support for the notion that lower childcare costs can have positive employment effects especially among single and younger mothers. However, we focus more on the concern that the costs of these programs will raise interest rates as debt levels reach a tipping point.

We allay debt fears by pointing out that this spending won’t add materially to the debt burden. It is instead intended to be paid for in almost equal amount by higher taxes and other provisions.

The blue bars in Figure 2 show these pay-fors by each of the next ten years. Total pay-fors aggregate roughly $3 trillion and provide a neat offset to the $3.5 trillion cost of the reconciliation bill.

How onerous will higher taxes be and what impact will they have on growth? Higher taxes account for 70% of total pay-fors or roughly $2.2 trillion. Most of the tax increases are projected to come from higher rates for domestic and international corporate taxes and high-income individual taxes.

We also don’t expect this higher tax burden to weigh significantly on economic growth … for one simple reason.

The restrictive effect of $2.2 trillion in higher taxes is likely to get neutralized by the expansionary effect of $3.5 trillion in higher spending.

We believe that the similar magnitude and inverse impact of higher taxes and higher spending could well offset each other and, therefore, be neutral to growth.

Inflection in Stimulus

The rapid recovery from the Covid recession was driven in large part by unprecedented levels of monetary and fiscal stimulus. The Fed has kept short-term interest rates at zero and expanded its balance sheet by more than $4 trillion. Government spending has also been monumental at $5.8 trillion in the last year and a half.

We are now on the cusp of an inflection point in stimulus. The Fed has clearly signaled its intentions to gradually embark on a tapering and then tightening cycle. The Fed is ready to scale back on its bond purchases and then raise interest rates.

And even though there is future spending proposed in the infrastructure and reconciliation bills, its magnitude pales in comparison to the post-Covid fiscal stimulus. The withdrawal of fiscal stimulus in this magnitude will create a so-called fiscal cliff and reduce future growth.

We assess the likely impact and implications of this shift in monetary and fiscal policy.

We believe that this expected shift in policy comes as no surprise to most market participants. The economic landscape in 2021 is far different than what it was in 2020. Ultra-stimulative policies were appropriate as emergency measures in the throes of a pandemic. But they are likely misdirected today in the midst of a healthy economic recovery and persistent inflationary pressures.

The minutes of the September Fed meeting suggest that it will likely begin to reduce its monthly asset purchases before year-end. This tapering process could see an initial reduction of $15 billion per month in bond purchases from the current monthly pace of $120 billion. It is expected that the target date to end bond purchases altogether will be mid-2022.

We concur that tapering should begin in November or December and last 6 to 9 months. We disagree, however, with the Fed’s latest forecasts for its pace and timing of rate hikes. Based on September data, the Fed projects no rate hikes in 2022 and 4 rate hikes in 2023.

We believe that interest rates need to rise sooner than in 2023. We believe that the strength of the economy, the recovery in the labor market and the persistence of inflation all argue for a liftoff in interest rates in the third quarter of 2022. In this regard, we are more aligned with the market than with the Fed. We remain vigilant for a policy misstep by the Fed in terms of falling behind the curve.

The absence of any “taper tantrums” in the markets so far suggest that these changes in monetary policy have been anticipated and priced in. Long-term interest rates have started to rise ahead of the Fed’s tightening plans.

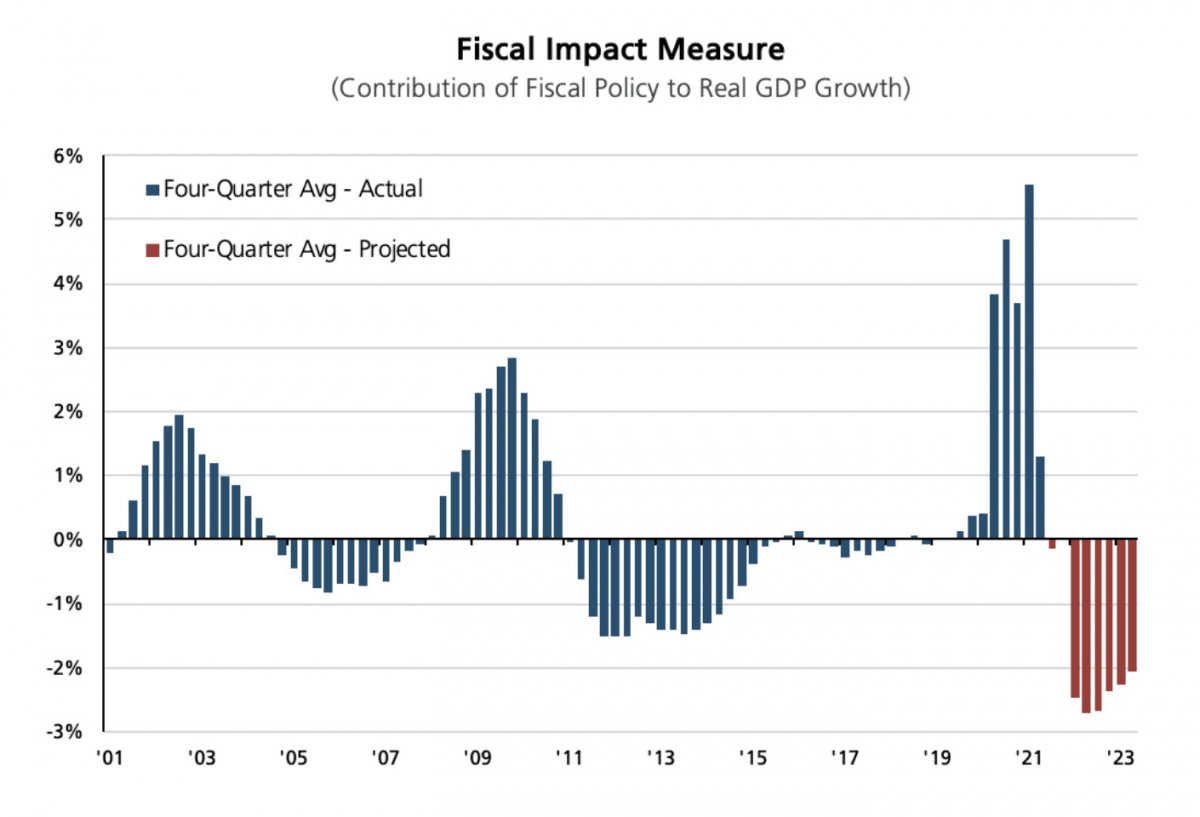

The impact of fiscal stimulus is generally less understood and is, therefore, worthy of more careful analysis. We measure the impact of fiscal policy on growth with a metric called Fiscal Impact Measure (FIM) developed by the Hutchins Center at Brookings Institution.

FIM is a more comprehensive metric than the federal deficit because it combines the impact of federal, state and local fiscal policy. It specifically measures the differential impact of fiscal policy beyond its normal level in an economy operating at potential GDP and full employment.

FIM is easy to interpret. By definition, it is zero and neutral to growth when government spending and taxes rise in line with potential GDP. When FIM is greater than 0, fiscal policy is expansionary … it pushes growth above potential GDP. Fiscal policy is contractionary when FIM is below 0.

We show the evolution of FIM in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Fiscal Impact Measure

Positive FIM levels are typically seen after recessions and they are particularly prominent on the right side of the chart in Figure 3. During the pandemic, fiscal policy was hugely expansionary and added between 4 to 6% to GDP growth.

By the same token, the end of that massive spending spree will create a negative impact on GDP growth in the next year or two. The red negative bars at the far right of Figure 3 show that growth will likely get reduced by a little more than -2%.

We expect that GDP growth will decelerate by -2 to -3% from the upcoming inflection in stimulus. However, we do not despair this drop-off in growth. At well above 3% in 2022, GDP growth will be considerably ahead of pre-Covid levels. In fact, we see these policy shifts as a reason to cheer and celebrate and not as a cause for concern. They simply mean that the U.S. economy is now self-sustaining and can be weaned off life-support measures.

We have already suggested that this upcoming deceleration of growth has been widely expected and is likely priced in. We lend credence to that notion by looking at the impact of decelerating growth on stock valuations.

Deceleration and Valuations

Many investors still worry that stock valuations are too high especially in the context of historical norms. A slowdown in growth is particularly troublesome to them because that would make valuations even less sustainable.

We allay those concerns by pointing out that this feared compression of PE multiples has already started to take place. Future earnings estimates have recently started to decelerate. But the markets had efficiently anticipated this deceleration well in advance of when it took place.

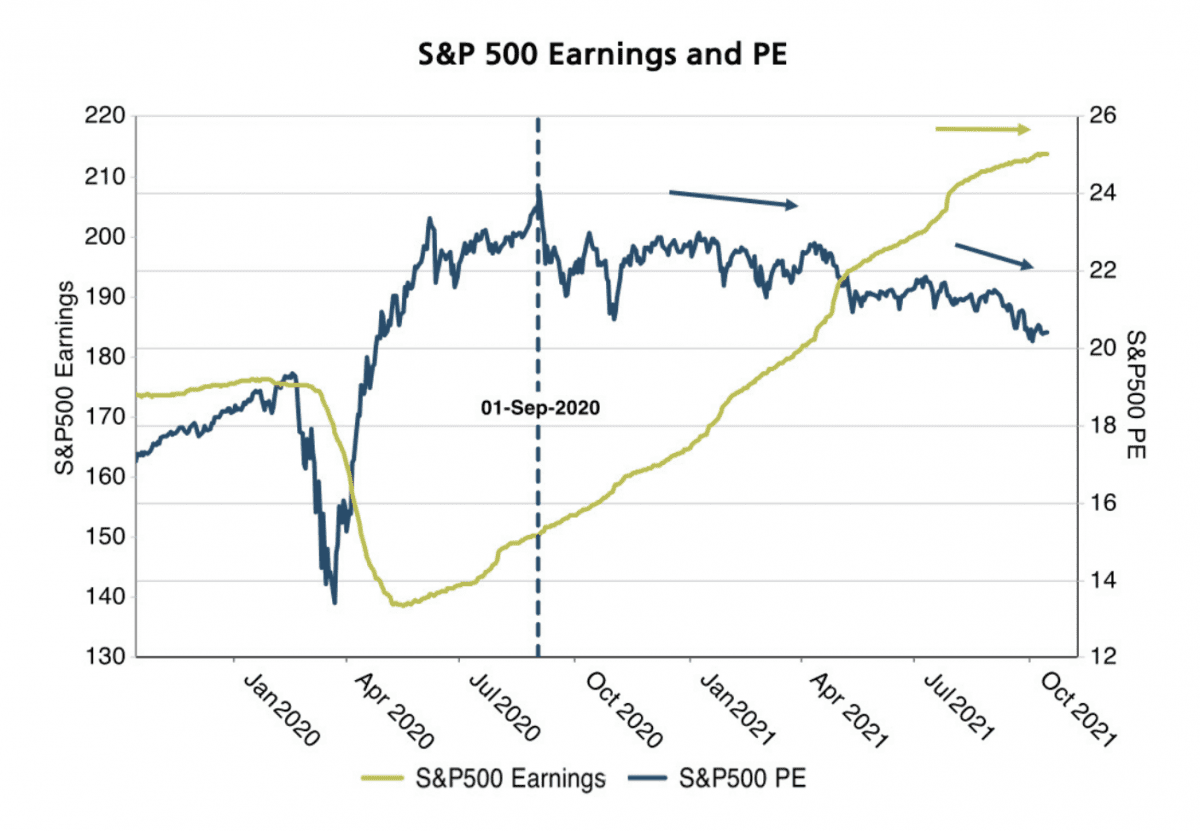

We show this vividly in Figure 4.

Figure 4: S&P 500 Earnings and PE

The green line in Figure 4 shows S&P 500 forward earnings and the blue line shows the S&P 500 forward PE multiple.

Forward earnings grew rapidly from the second quarter of 2020 and have recently started to grow at a slower pace. PE ratios have correctly anticipated both the initial burst of growth and then the subsequent deceleration … and well in advance by several months.

The current deceleration in earnings growth began to take shape in September 2021. It is remarkable that PE ratios began to price in this eventual deceleration one full year earlier in September 2020! The forward PE ratio peaked at that time at around 24 times. It has continued to compress even as earnings continued to rise but at a progressively slower pace. The forward PE ratio now stands at around 20 times.

We reiterate our belief that the impending slowdown in growth is not a new development and certainly not a surprise for the markets. We also believe that even though PE multiples have come down, they will continue to modestly compress further in the next year or two.

We believe that current stock valuations are reasonable in light of still-low interest rates and above-average growth. We believe that future earnings growth and dividend yields will offset this continued compression of PE multiples and generate positive equity returns.

Summary

We examined a number of concerns that are currently weighing on investors – Delta variant, debt ceiling, inflation, spending and taxes, inflection in stimulus, deceleration of growth and stock valuations.

We do not believe that these factors, individually or collectively, will conspire to significantly disrupt growth. We don’t dismiss them as trivial distractions either. Between the bookends of major disruptors and mere distractions, we position them as modest detractors of growth.

We summarize several beliefs, views and thoughts on this broad array of topics as follows.

- The Delta variant and future virus strains will have limited economic impact

- Inflation will remain stubbornly persistent over the next 12 months or so; it will eventually become transient as it drops below 3% by 2024

- Higher taxes and spending will offset each other … and be neutral to growth

- The Fed has signaled that tapering will begin by year-end and end in mid-2022

- We expect the first rate hike to happen earlier than current Fed projections … we may see a liftoff in interest rates in Q3 2022

- Fiscal and monetary inflections will cause growth to decelerate by -2 to -3%; however, growth will still be robust in 2022 and 2023

- Inflection in stimulus is not new information and is likely priced in

- Stock valuations have already compressed … and will do so in 2022 as well

We believe that this new economic cycle and bull market have longer to run. Our constructive outlook lends itself to a pro-growth, pro-cyclical tilt in our asset allocation and portfolio positioning.

We are also mindful that we have just come through some truly unprecedented times and uncertainty still abounds. We, therefore, remain respectfully vigilant and cautious in our optimism.

Investors are worried that stubborn inflation, higher taxes and the end of monetary and fiscal stimulus may become major disruptors of growth.

We believe that is unlikely to happen.

From Investments to Family Office to Trustee Services and more, we are your single-source solution.