The Big Central Bank Dilemma

The U.S. economy and capital markets continued to surprise investors through the first half of 2024. The year began with high hopes that the rapid disinflation of 2023 would continue in an orderly and uninterrupted manner. This in turn spurred optimism that the Fed would be able to cut rates as early as in March. At that stage, the consensus expectation for monetary policy was 6 to 7 rate cuts in 2024 alone.

These hopes were dashed in the first quarter as inflation readings came in higher than expected. The economy remained unusually resilient as job growth and consumer spending exceeded expectations. In a matter of just

a few months, the timing of rate cuts has changed dramatically. In early July, the Fed’s projections called for just one rate cut in 2024; the market was pricing in two. Not surprisingly, bond yields have also remained higher; most bond market indices generated flat returns in the first half of 2024.

Under normal conditions, such a hawkish pivot in monetary policy might also have derailed stocks, especially at their loftier valuations during most of 2024. Instead, U.S. stocks performed remarkably well in the first half of 2024. The S&P 500 index rose by 15.3%, the Nasdaq 100 index surged 17.5% and the Russell 3000 index gained 13.6%.

Even as monetary policy expectations disappointed, the stock market derived its strength from stellar earnings growth. Most investors were caught flat-footed by their belief that the consensus double-digit earnings growth rates for 2024 and 2025 were simply too high. On the other hand, we had formed the minority view in our 2024 outlook that not only were these earnings levels likely to be achieved, but they could even be exceeded. Stocks handily outperformed bonds in alignment with our tactical positioning.

The resilience in economic activity and inflation at the beginning of the year gave rise to a new theory in support of higher-for-longer interest rates. By historical standards, a Fed funds rate of 5.4% should have been significantly restrictive in slowing the economy down. In fact, many had expected the 11 rate hikes in this tightening cycle to cause a recession by 2024.

A plausible explanation for the muted impact of higher interest rates is that the post-pandemic economy is operating at a higher speed limit. This possibility has several implications. It suggests that the neutral policy rate to keep this economy in equilibrium is also higher. If this were true, then the actual policy rate is not nearly as restrictive as what history would suggest. A higher neutral rate also suggests that eventual Fed easing won’t be as significant as expected. And finally, in this setting, all interest rates would end up higher than expected as well. We explore the possibility of a change in the neutral rate in our analysis.

Recent economic data, however, is now beginning to reverse. The last couple of months have seen renewed evidence of cooling inflation, a weaker job market and a softer economy. By the end of the second quarter, both headline and core inflation had receded to 2.6%, the unemployment rate had risen above 4% and real GDP growth in 2024 was tracking below trend at around 1.5%.

This recent decline in inflation and economic activity poses a difficult dilemma for the Fed. As long as growth was resilient, the Fed had the option to remain patient and keep rates high. Indeed, their policy so far has focused on avoiding the policy mistakes of the late 1970s. If they ease too soon, a potential surge in economic activity might rekindle inflation and send it higher.

However, as growth deteriorates and inflation heads lower, the risks of waiting too long may now outweigh the benefits of being patient. Several sectors of the economy remain vulnerable to the prolonged impact of higher interest rates. These include the highly leveraged private equity and commercial real estate businesses and the less regulated private credit markets. The balance of risks may well tilt towards growth and away from inflation. The Fed is clearly focused on this dynamic; Chairman Powell began his semi-annual July congressional testimony by observing that “reducing policy restraint too late or too little may unduly weaken economic activity and unemployment.”

As a result, the Fed finds itself at a crucial juncture in formulating future monetary policy. In addition to getting the timing of rate cuts right, it also needs to assess the proper neutral rate in this new cycle to calibrate the eventual magnitude of easing.

We focus our article on fully understanding this big central bank dilemma. We offer policy recommendations that may yet allow the Fed to thread the needle and engineer a soft landing. Finally, we juxtapose the Fed’s likely course of action with the divergent easing paths of foreign central banks.

- Is there a new neutral rate at play? How has it changed? What are its policy implications?

- When should the Fed make its first rate cut? How many should they do? At what speed?

- What are the implications of divergent central bank easing policies across regions?

The Neutral Rate

We have previously written about how the U.S. economy is now less rate-sensitive than ever before. Consumers and corporations alike have locked in low fixed rates well into the future; they are more immune to rising rates than they were in the past.

However, the unexpected resilience of the U.S. economy is also starting to spur a new theory about future Fed policy. The key concept in this line of thinking is the so-called neutral interest rate. First, a quick definition. The neutral rate is the equilibrium policy rate that allows an economy to achieve its full potential growth at stable inflation. In other words, it is the steady-state policy rate that is neither restrictive nor accommodative; it is neither expansionary nor contractionary.

While it is intuitive, a major practical limitation of this framework is that the neutral rate is unobservable and, therefore, cannot be measured. It can only be estimated ex-ante; it is eventually validated ex-post by trial and error from actual realized outcomes of growth and inflation.

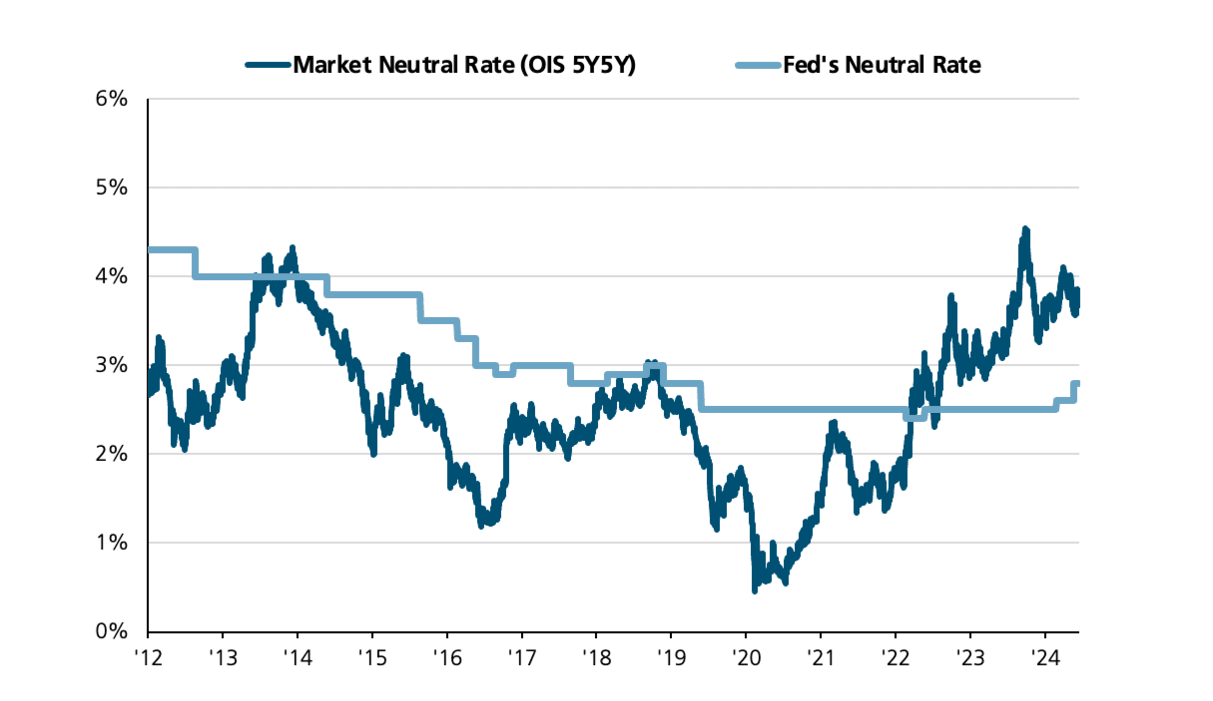

Many believe that the neutral rate is now permanently higher. They, therefore, contend that there are far fewer rate cuts ahead of us. The more profound implication of this assertion is that higher rates may prevail forever, not just for longer. Market expectations have clearly moved in this direction. We see this in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Market Expects A Higher Neutral Rate Than The Fed Does

Source: Bloomberg, FactSet

The navy line in Figure 1 depicts the market’s estimate of the neutral rate. It is derived from a useful, but less widely followed, measure of future expected risk-free rates. We describe this technical metric as simply as possible and explain how it becomes the market’s proxy for the neutral rate.

The Overnight Index Swap (OIS) is a useful tool to hedge interest rate risk and manage liquidity. For our purposes here, we can think of the OIS rate as the fixed rate for which one is willing to receive a floating rate in exchange. This floating rate is typically tied to an overnight benchmark index such as the Fed Funds Effective Rate. The OIS 5y5y rate shown as the navy line in Figure 1 can be interpreted as the fixed rate for a period of 5 years, starting 5 years from now, at which one would be willing to receive the overnight floating rate in exchange.

In its simplest form, it reflects the market’s projection of the average overnight or risk-free rate over a 5-year period, which begins 5 years from now. Because the OIS 5y5y rate is a proxy for the overnight rate in the longer run, it is the market’s estimate of the neutral policy rate.

The setup for defining the market neutral rate was tedious, but analyzing it is fascinating. Before we do so, here is a quick and far simpler word on the light blue line in Figure 1. It is the Fed’s projection of the long-term or neutral policy rate.

In Figure 1, we see that the market neutral rate has long been anchored by the Fed’s estimate of the neutral rate. Since 2012 in the post-GFC era, the market neutral rate (navy line) has consistently remained below the Fed’s neutral rate (light blue line).

This trend has reversed in the last two years. In recent weeks, the overnight swaps market has been pricing the neutral rate at just below 4% (e.g. it was 3.7% on July 8). On the other hand, the Fed’s long-held estimate of the neutral rate has been 2.5%; the Fed has now revised it up to 2.8% as of June 2024.

The market neutral rate burst above the Fed’s neutral rate in early 2022. We believe the initial 2022 spike in the market neutral rate was driven by expectations of higher inflation. We believe its subsequent rise in the last 12 months has been fueled by expectations of long-term economic resilience.

The Fed’s policy rate is currently at 5.4% and the true neutral rate will determine how low it can go. If the market is correct about the new neutral rate being closer to 4%, cumulative Fed easing will be a lot less than what may have happened in previous regimes of a lower neutral rate.

We offer our own view on where the new neutral rate may emerge in the coming months. We believe it is higher than the Fed’s 2.8% projection, but it is nowhere close to the market’s expectation of around 4%.

As we mentioned at the outset, the neutral rate is unobservable and hard to measure. But we do know that the nominal neutral rate is influenced by inflation. It is also affected by changes in the trend growth rate. We believe each of these factors will be higher in the next cycle and create a new neutral rate of 3.0-3.2%.

We have maintained for a couple of years now that the Fed’s 2% inflation target will likely be elusive. An aging population, along with new potential immigration barriers, will constrain the supply of labor and create a higher floor for wage inflation. We also believe that impediments to global trade in the form of tariffs and a populist mindset of de-globalization will potentially lead to higher inflation. We expect trend PCE inflation to settle at 2.3-2.4%.

We also expect a small increase in trend GDP growth. We have seen a recent rebound in productivity growth; we expect this to become a more secular trend as technology, AI, robotics and automation drive further productivity gains. We also expect the U.S. economy to be modestly more resilient and impervious to higher inflation and interest rates.

We summarize this section with the following observations.

- We believe a new neutral rate is at play in this economic cycle.

- It is higher than the Fed’s estimate of 2.8%, but well short of the market’s expectation of 3.7%. We peg it to be around 3.0-3.2%.

- The market may be mistaken in expecting significantly higher trend inflation or trend GDP growth.

- Technology remains a powerful disinflationary force.

- Increases in trend GDP growth will inevitably be bounded by a slowing labor force and only modest productivity gains. The market may be erroneously extrapolating recent economic resilience too aggressively, too far out into the future.

Future FED Policy

Magnitude of Rate Cuts

Our discussion on the likely neutral rate going forward makes it easier to anticipate future Fed policy. The Fed funds rate is currently at 5.4%; we estimate the new neutral rate to be 3.1%. We believe this leaves room for 8 to 9 rate cuts in the next 18 to 24 months. The speed at which the Fed is able to implement these rate cuts will depend on how rapidly inflation and economic growth can cool off.

Timing and Trajectory of Rate Cuts

We preface this discussion with our most startling takeaway. We believe the timing and trajectory of rate cuts, to a large extent, will simply not matter. In many ways, we already have evidence to that effect; they haven’t mattered so far in 2024. Expectations for rate cuts this year have gone down from 6 starting in March to just 2 now by December. And yet, the stock market has been strong; the S&P 500 index was up more than 15% through June.

Our logic for this assessment is simple. As long as the market can anchor to the total magnitude of likely rate cuts based on an understanding of the neutral rate, it will likely look through the timing of the first rate cut and the subsequent speed of the next few.

We, nonetheless, believe that the following sequence of rate cuts may be optimal in balancing both inflation and growth risks.

- We see sufficiently softer inflation and growth to implement the first rate cut in September and two more by December 2024.

- We believe the Fed can get to a neutral rate of 3.0- 3.25% before the end of 2026.

- We hold out the caveat that no Fed action for the next 6 months would be a policy misstep.

![]() Global Central Bank Divergence

Global Central Bank Divergence

Global central banks have been remarkably coordinated and synchronized since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. All of them eased immediately and dramatically to support economic growth during the global lockdowns. Post-pandemic inflation, induced by this flood of liquidity, was also a global phenomenon, which then led to a synchronized global tightening cycle.

As inflation and growth begin to cool down across the world, there is some angst that global monetary policy will not be fully in sync during the upcoming easing cycle. We have already seen this happen. The Fed is still on the sidelines awaiting its first rate cut. In the meantime, the Swiss National Bank has already cut rates twice this year, the European Central Bank (ECB) has eased once, the Bank of England hasn’t moved yet and the Norges Bank has indicated that they won’t ease until 2025.

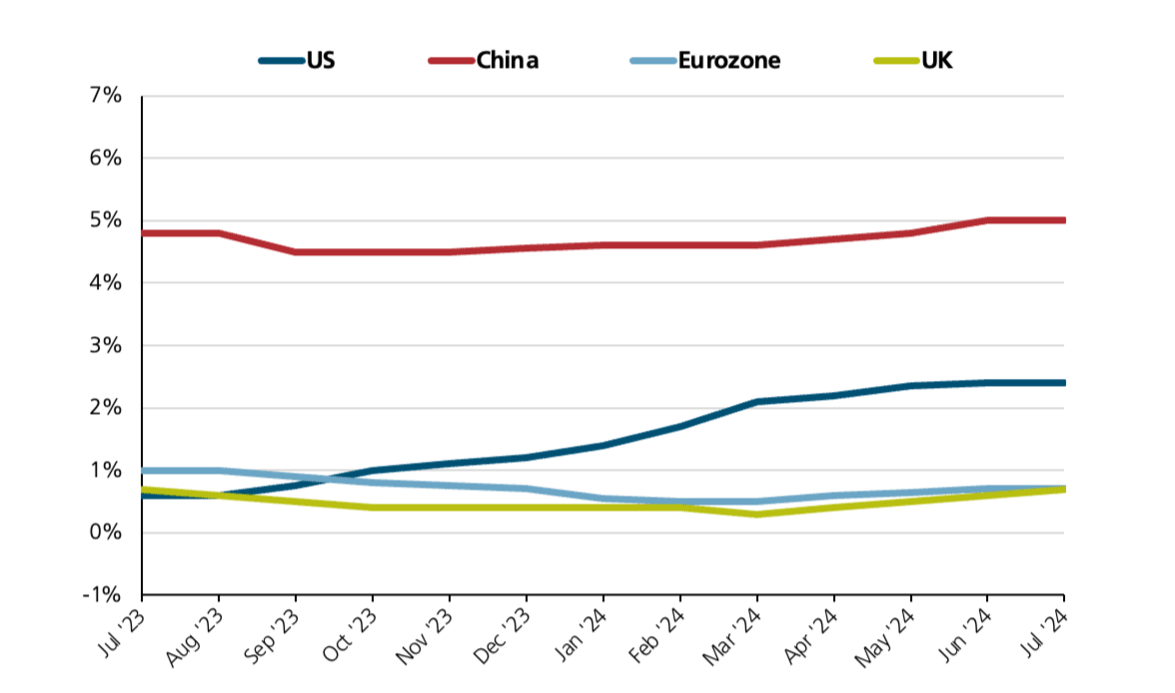

We believe that the more disjointed global easing cycle is actually justified from a fundamental perspective. These differential easing paths are largely being driven by different growth dynamics across the world. We see this in Figure 2.

Figure 2: 2024 Real GDP Growth Estimates Across Regions

Source: FactSet

Recent GDP growth has been higher in the U.S. than in Europe. It is no surprise, therefore, that the Fed has more flexibility to ease at a slower pace than the ECB does.

We still expect the overall trend towards easing to be consistent across central banks. We believe that the Bank of Japan will be the only major central bank that won’t cut rates by the end of 2025. Many others will begin to do so in 2024. A global easing cycle is about to begin and global short rates are expected to decline by almost 150 basis points over the next 18 months.

We believe stronger growth fundamentals will continue to favor U.S. stocks and the U.S. dollar. As a convenient and desirable byproduct, the strength in the U.S. dollar will continue to be disinflationary and bolster the case for a sustained Fed easing cycle.

![]() Summary

Summary

We explored several nuances of the upcoming central bank dilemma. We examined the prospects of a new neutral rate for the U.S. economy, the magnitude and timing of likely Fed rate cuts and the potential for any adverse effects from divergent easing across global central banks.

We summarize our key takeaways below. We believe:

- There is a new and higher neutral rate of 3.0-3.2% for the U.S. economy in this cycle.

- While above the Fed’s long-held view of 2.5%, our estimate of the neutral rate is well below market expectations of around 4%.

- The market is likely overestimating the neutral rate by extrapolating significantly higher trend inflation or trend GDP growth.

- With the Fed currently at 5.4%, our 3.1% estimate of the neutral rate leaves room for 8 to 9 rate cuts in the near term.

- Inflation and growth dynamics suggest that the Fed can get to the neutral rate in 18 to 24 months.

- As long as the markets can anchor to the likelihood of 8-9 rate cuts in aggregate, the actual timing and trajectory of Fed rate cuts will not matter to a large extent.

- We see enough weakness in inflation and economic growth to advocate the first rate cut in September and two more by December 2024.

- No Fed action for the next 6 months will likely constitute a policy misstep.

- Global monetary policy is likely to be less synchronized in the upcoming easing cycle, but not in a materially adverse manner.

We have been increasingly confident that high inflation and interest rates will soon subside. We also remain confident in the earnings outlook. With the tailwinds of accommodative monetary policy and strong earnings growth, we rule out a bear market scenario or even a prolonged correction for U.S. stocks.

Our sustained risk-on positioning in the last two years has worked well. We maintain a similar, but more modest, posture going forward. We continue to exercise prudence in managing client portfolios.

To learn more about our views on the market or to speak with an advisor about our services, visit our Contact Page.

We believe there is a new and higher neutral rate of 3.0-3.2% for the U.S. economy in this cycle.

We believe the market is grossly overestimating the neutral rate at around 4%.

With the Fed funds rate at 5.4%, our 3.1% estimate of the neutral rate leaves room for 8 to 9 rate cuts in the next 18 to 24 months.

From Investments to Family Office to Trustee Services and more, we are your single-source solution.